Location: Corner of North Main and School Streets, North Brookfield

Coordinates: 42°16’06.0″N 72°05’04.0″W

Date dedicated: January 19, 1870

Architect/design: Martin Milmore of Boston

The rural town of North Brookfield managed to land one of New England’s most prestigious sculptors to create their monument and secured the attendance of Governor Charles Claflin as well as General Charles Devens (one of the state’s top generals) for the dedication exercises. The event was major news and attracted an unusual degree of attention for such a small town. Two important figures from North Brookfield seem to have been responsible for this: Charles Adams, Jr., a prominent resident and influential member of the Massachusetts Republican Party who served in both the House and the Senate of the state legislature, and Brevet Brigadier General Francis Amasa Walker who commanded widespread respect for his service record during the war.

Walker gave the main oration on the occasion. This was published and stands out among such speeches as remarkable for its candor and the ways in which he undermined lofty notions of causes like liberty, glory, and union. He criticized glory-seeking generals and instead celebrated the soldiers’ simple perseverance, describing their many sufferings with surprising detail. More on this unusual address in a bit.

First, as for the monument itself, Charles Adams, Jr., chair of the monument committee, approached Martin Milmore in 1869 and asked him to create a facsimile of his much lauded Roxbury Soldiers’ Monument (see that city’s article for more information). Milmore essentially pioneered the “standing soldier” form in New England. He was not the only sculptor working on this form, but to Bostonians (and by extension much of Massachusetts) he was the best known. Milmore immigrated to this country as a youth, brought over by his mother. He went into the stone cutting business in Boston with his brother and soon had a successful studio. His design of Boston’s Soldiers’ and Sailors’ monument put him in the national spotlight three years after North Brookfield’s was dedicated. But his Roxbury monument is seen by many, including this author, as his finest work.

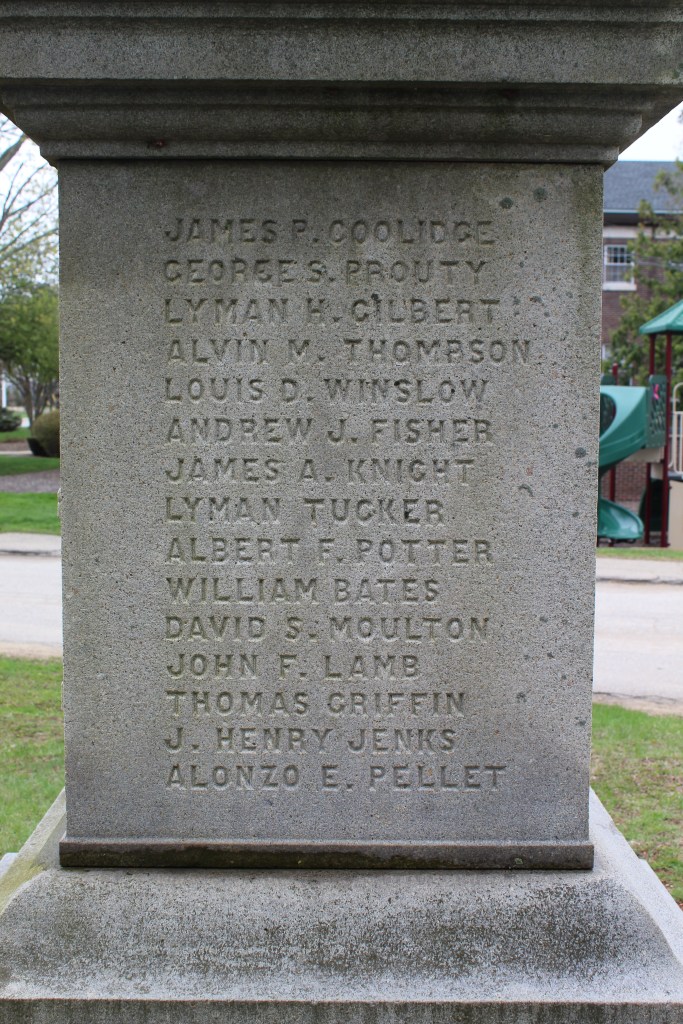

Milmore evidently selected the stone himself directly from the Concord, New Hampshire quarry wall before it was cut.[1] The inscription reads, “Erected by the Town of North Brookfield in honor of her soldiers who lost their lives in defense of the country against rebellion, 1861 – 65.” It records the names of the 31 war dead. Fourteen of them, Walker explained in his address, died in battle or of battle wounds. Three of these belonged to the 15th Massachusetts who died in the span of a half hour during that unit’s infamous fight in the West Woods at Antietam when the regiment was virtually surrounded. Sixteen died of disease, including four in Andersonville Prison. And one was shot for desertion. That his comrades voted to include his name on the monument indicates that there is a story there, and Walker explained in his address.

General Francis Walker’s address was so frank, so unusual, a much longer piece could be written about it to explore its themes. Here, a summary of some key points will have to do. He began with a jarring condemnation of glory-seeking generals. And he named names. He said he was thankful that there were no great and famous soldiers present that day (General Devens might have shifted in his seat at that one) as it would overshadow the humble heroism of North Brookfield’s very average soldiers. None of them, he said, had distinguished themselves in any marked way except for the devotion and perseverance they showed in serving through trials day after day. Glory was meaningless, he suggested. “It is even more a duty, sometimes, to go without shrinking into what you know to be not a battle but a butchery,” Walker said, “…the more unfortunate the country in its commanders, the more need to have brave and devoted soldiers.”[2]

He unleashed a dramatic and lengthy curse against slavery. In doing so, he comes off not so much as an abolitionist, but a man with a deep hatred for slaveholders for starting a war to protect their institution that resulted in so much agony and bloodshed. “It was slavery that crowded our brothers and our sons into those foul prison pens; it was slavery that denied them every comfort and decency of life…[he goes on with descriptions of suffering and violence for some time]…It was…slavery that did these deeds of hell… Cursed, forever accursed, be the thought and name of human slavery.”[3]

Walker also told the story of Private William Hill of the 20th Massachusetts and a resident of North Brookfield. Hill was shot for desertion on August 28, 1863. Walker explained that the veterans of the town voted to include his name on the monument (something highly unusual for a man executed for desertion) because the circumstances of his conviction were flawed. Walker called it, “an act of mistaken policy, if not of actual injustice” and by including his name, they meant no disrespect to the other fallen. Walker indicated that the “character of [Hill’s] mind” was such that he was not responsible for the confusion that led to him leaving his post.[4] He seems to suggest that Hill had a mental disability. Further, after a period of laxity when it came to desertions, the high ranking officers at that time sought to crack down on soldiers leaving their posts and made an example of Hill. Walker actually admitted that he signed Hill’s conviction but did not realize who the soldier was…and that if he had, he surely could have cleared the matter up. All this represents what must have been a weighty confession and a sad realization for those present at the address.

As for the ultimate meaning of the monument, Walker asked that there be no talk of “proclamations and constitutional amendments, reconstruction and suffrage.”[5] Instead, he asked his community to simply remember the fallen and remember what they suffered.

…When we stand before such a memorial stone as this we dedicate to-day, we realize what war means; we see here what glory costs. There were thirty young men in this remote and peaceful village who must die for nothing else than that there was war — husbands, sons and brothers…While we grudge not that which we did and suffered for union and liberty, may we fully resolve that nothing but an equal necessity shall ever again call for such contributions and sacrifices. Let this monument to our deceased brothers keep always before our minds this lesson of the horror and mischief of war.[6]

[1] Springfield Weekly Republican, January 22, 1870.

[2] Francis Amasa Walker, An oration delivered by Gen’l Francis A. Walker, at the Soldiers’ monument dedication in North Brookfield, Jan. 19, 1870 (Worcester, MA: Goddard & Nye Printers, 1870), 9.

[3] Walker, 13.

[4] Walker, 18.

[5] Walker, 20.

[6] Walker, 20.